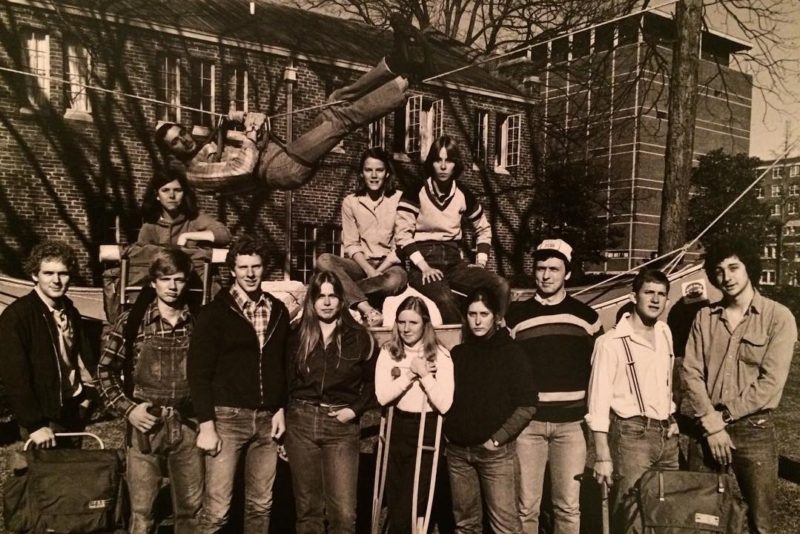

The Founding Fathers

WilSkills came to be in the fall of 1974 when graduate student Kimball McKee approached Vanderbilt administrators with the idea of creating a Wilderness Skills Course based on the example of the Outward Bound Schools. A Housing Director, Robert Warren, started publicizing and recruiting instructors while McKee began to compile a budget and contacted University Provost Nicholas Hobbs in order to secure funds for the course.

Kimball McKee approached Vanderbilt administrators with the idea of creating a Wilderness Skills Course based on the example of the Outward Bound Schools.

The group was not dissuaded and in May of 1975, $3500 from the Provost’s Contingency Fund were credited to the “Outdoor Education Program.”

The Wilderness Skills Course was designed to integrate study in the academic disciplines with interpretation of and physical experience in the natural world.

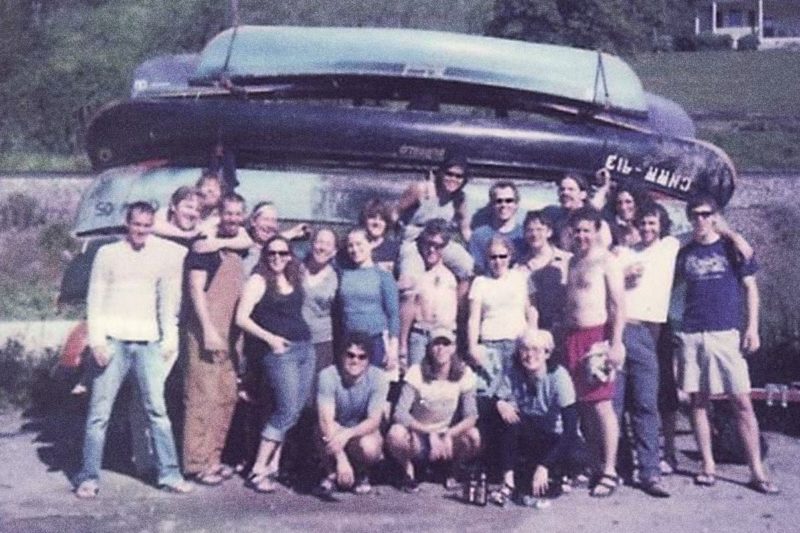

These trips were designed to test the skills demonstrated to the students during the lectures.

The lectures were presented by members of the Vanderbilt faculty, personnel from the Tennessee Department of Conservation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, Sierra Club, National Speleological Society, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, American Red Cross, and the Tennessee Scenic Rivers Association. They covered topics such as basic first aid, weather and climate, hydrology, caving, TVA, basic survival skills, the geology of the southern Appalachians, endangered species, the politics of wilderness preservation, and parks and pocket wildernesses in Tennessee.

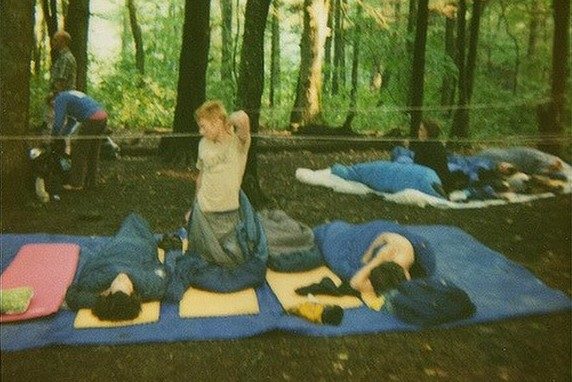

The field trips were primarily designed to teach students the basic techniques of backpacking, white water canoeing, caving, and rock climbing.

As man is not only an explorer, but the product of the natural world, students were taught the proper methods of coexistence with the environment

experience nature on its own terms, develop self-discipline, and participate in the formation of functioning communal relationships.

Philosophically, the program assumes that people develop a greater reverence for life having experienced it in real and dramatic terms

short, intensive encounters with problems and the attempts to resolve them can have a long-term impact upon one’s life.